OSTEOPOROSIS: The Myth of Diagnosis & the Reality of Prevention and Treatment

Comments and Summary

Ronald Peters MD

Osteoporosis is much more complex than most doctors would lead you to believe. Consider the following from the medical research:

DEXA Bone Density Scan measures bone mass (quantity), not bone strength (quality) (Susan Ott, MD, specialist in metabolic bone disease University of Washington Medical Center)

DEXA Bone Density Scan measures bone mass (quantity), not bone strength (quality) (Susan Ott, MD, specialist in metabolic bone disease University of Washington Medical Center)- 54% of the 243 hip fractures occurred in women did not have osteoporosis (US Study of Osteoporotic Fractures)

- “BMD testing is unable to accurately distinguish women at low risk of fracture from those at high risk” (British Columbia Office of Health Technology)

- Of 7.8 million people diagnosed with osteoporosis, only 4.3% experienced a clinically recognized fracture (The Bone EVA study, Germany)

- 82% of women who fractured did not have a BMD diagnosis of osteoporosis (The NORA study of 150,000 postmenopausal women)

- after 6 years of treatment with bisphosphonates (Fosamax) – risk of fracture in those taking the medication was the same, or higher, that the group that took no medication

Initiating drug therapy for osteopenia, or osteoporosis, without empowering the patient to understand the many lifestyle factors that create weak bones is another example of the excessive and simplistic reliance on drug therapy in modern medicine.

As I began to write about the limitations of the DEXA scan in diagnosis and the problems with drug therapy alone, I found the following article by Sandra Boodman published in the Washington Post, which summarizes the limitations of the current medical model regarding osteoporosis and treatment.

IF YOU WANT PERSONALIZED GUIDANCE IN RISK ASSESSMENT, LIFESTYLE CHANGES, A RANGE OF EFFECTIVE BIOIDENTICAL HORMONE THERAPIES AS WELL AS NUTRIENT THERAPIES, PLEASE MAKE AN APPOINTMENT AT MINDBODY MEDICINE CENTER – 480.607.7999

Hard Evidence By Sandra G. Boodman, Washington Post, September 26, 2000,

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/wellness/2000/09/26/hard-evidence/b34cd025-7898-4b7d-9fe6-7dee2dc241cb/

It may not be the disease women fear most, but that’s not for lack of publicity.

In the past decade, a multi-billion-dollar industry has sprung up devoted to preventing, diagnosing and treating osteoporosis–thin, brittle bones that tend to fracture easily. That’s remarkable for a condition most people had never heard of 15 years ago.

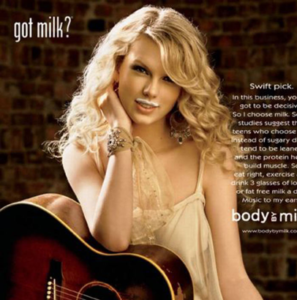

These days it’s hard to open a magazine or turn on the television without seeing ads for prescription drugs, pitched by actresses of a certain age, aimed at combating fragile, porous bones. There are stories about the threat osteoporosis poses to aging women, next to ads that are part of the ubiquitous milk mustache campaign. Bookstore shelves are laden with such self-help books as “The Super Calcium Counter” and “Strong Women Stay Young.” Supermarkets and drugstores bulge with an expanding array of calcium-enriched foods–chewy candy supplements, breakfast cereals, bread, pancake mixes and juices, as well as over-the-counter “natural” remedies that trumpet “bone health.”

These days it’s hard to open a magazine or turn on the television without seeing ads for prescription drugs, pitched by actresses of a certain age, aimed at combating fragile, porous bones. There are stories about the threat osteoporosis poses to aging women, next to ads that are part of the ubiquitous milk mustache campaign. Bookstore shelves are laden with such self-help books as “The Super Calcium Counter” and “Strong Women Stay Young.” Supermarkets and drugstores bulge with an expanding array of calcium-enriched foods–chewy candy supplements, breakfast cereals, bread, pancake mixes and juices, as well as over-the-counter “natural” remedies that trumpet “bone health.”

The message is unequivocal: Women (and some men) need to take action before it’s too late to avoid developing the insidious, crippling disease that has struck an estimated 10 million Americans and can result in a hip fracture, a dowager’s hump, an aching back, loss of height, and death in a nursing home.

Consider this recent full-page ad in Parade magazine featuring a slim, athletic-looking fortysomething model posing as “Hannah Thomas,” an office manager who does yoga, “eats healthy, uses the Internet”–and worries about osteoporosis because she’s on the brink of menopause. She takes the estrogen drug Prempro largely because, as the ad warns ominously, “you can be in the early stages [of osteoporosis] and not even know it.”

Then there’s a two-page spread for the osteoporosis drug Evista in Ladies’ Home Journal. The ad features actress Julie Andrews, 64, clutching two bulky pots of rosebushes and proclaiming, “I’m not about to give up doing my favorite things.” But, Andrews cautions, osteoporosis can “fracture your health and independence”: Just walking down a flight of stairs could mean a broken bone.

And here’s actress Rita Moreno, 68, the newest spokeswoman for the “Stay Strong! Test Your Bone Strength” campaign. The campaign is underwritten by Merck, maker of Fosamax, the world’s leading osteoporosis drug, which last year recorded sales of more than $1 billion. Moreno recently told the Orlando Sentinel that failure to take a bone density test is “absolutely criminal,” since the noninvasive test takes only 10 minutes and can, she says, avert a dreaded disease.

And here’s actress Rita Moreno, 68, the newest spokeswoman for the “Stay Strong! Test Your Bone Strength” campaign. The campaign is underwritten by Merck, maker of Fosamax, the world’s leading osteoporosis drug, which last year recorded sales of more than $1 billion. Moreno recently told the Orlando Sentinel that failure to take a bone density test is “absolutely criminal,” since the noninvasive test takes only 10 minutes and can, she says, avert a dreaded disease.

“I’m all for scaring women when it comes to health,” Moreno recently told the Chicago Tribune.

Just how big a threat does osteoporosis really pose to the tens of millions of female baby boomers approaching or just beyond 50, the average age of menopause, and their older sisters?

Does the difference between a vigorous, independent old age and shuffling, hunchbacked dependence in a nursing home really lie in getting a bone density test and starting a drug as early as your late forties in the hope of averting a broken bone 20, 30 or 40 years later?

Interviews with women’s health advocates and osteoporosis experts suggest that the answers to these questions are considerably more complicated, and less clear-cut, than some public service campaigns, calcium supplement pitches and drug ads suggest. These skeptics acknowledge that osteoporosis is a serious and potentially devastating medical problem–one that is likely to increase in incidence and importance as more Americans live longer. But they say it has also been the subject of considerable hype and confusion fueled by drug companies and other firms pushing products and by some advocates seeking to raise awareness of their cause.

“I think even people who agree that osteoporosis is a serious public health problem can still say it’s being hyped. It is hyped,” said Mark Helfand, director of the Evidence-Based Practice Center at Oregon Health Sciences University in Portland. “Most of what you could do to prevent osteoporosis later in life has nothing to do with getting a test or taking a drug,” added Helfand, a member of a National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus panel that spent three days last March conferring about the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis.

“What’s troublesome about all this publicity is that osteoporosis is getting visibility out of proportion” to its significance, said Deborah Briceland-Betts, executive director of the Older Women’s League, a Washington-based advocacy organization active in health education. As a result, she said, other common and equally serious health problems such as heart disease and obesity have received short shrift.

“There’s a whole group of people who don’t need intervention, other than advice about eliminating risk factors, which everyone should get,” agreed Robert Lindsay, a New York internist and one of the founders of the National Osteoporosis Foundation.

Osteoporosis “is a work in progress, and we tend to jump ahead with a little bit of data,” noted breast cancer surgeon Susan M. Love, a women’s health activist. “There’s a lot of fear-mongering going on. You don’t want people to say that osteoporosis isn’t a problem, because it is. But on the other hand, calling osteoporosis a disease is like calling high cholesterol a heart attack. Cholesterol is a risk factor for heart attack, but it’s probably not the whole story. It’s the same thing with osteoporosis; low bone density is probably not the whole picture” in determining who gets fractures and who doesn’t.

Wyeth-Ayerst spokeswoman Audrey Ashby said that the company’s promotion of Prempro using pre-menopausal women is appropriate. “It’s an ad that encourages women to talk to their health care provider about estrogen loss at menopause. The objective is to have women enter into a dialogue with their health care provider and make an informed decision. This is not necessarily a decision you make the day you reach menopause; it encourages women to think about their treatment options beforehand.”

Sandra C. Raymond, who was instrumental in transforming the National Osteoporosis Foundation from a small interest group that she helped launch in 1986 into a powerful advocacy organization with an annual budget of about $10 million (about 25 percent of it from drug companies, she said), asserted that osteoporosis for years suffered from a dearth of attention.

Sandra C. Raymond, who was instrumental in transforming the National Osteoporosis Foundation from a small interest group that she helped launch in 1986 into a powerful advocacy organization with an annual budget of about $10 million (about 25 percent of it from drug companies, she said), asserted that osteoporosis for years suffered from a dearth of attention.

“I don’t think this has been hyped any more than breast cancer has been hyped,” Raymond said. “It’s a very common disease, and women are at very high risk. We’re not trying to scare women, but we’re trying to tell them there are things you need to look at, steps you can take to prevent it. I think if you’ve got a preventable disease, you can’t hype it too much.

“And I don’t think that all the women at 50 who are told they have low bone mass are running to get a drug,” she added.

Because women are increasingly bombarded with scare stories and scarier statistics, many of them promulgated by interested parties, osteoporosis is a condition badly in need of a reality check.

What follows is an attempt, based on interviews with two dozen osteoporosis experts and women’s health advocates, to separate the hype from the hard evidence, to put the statistics about risk in context and to debunk some of the most common myths surrounding this increasingly high-profile medical problem.

MYTH #1

The More Calcium, The Better

It’s easy to see how this one got started, because innumerable studies have shown that American diets are woefully deficient in calcium, the main building block of bone. Calcium is essential at all stages of life, for building bone mass early in life and for reducing bone loss thereafter. Only 10 percent of girls between the ages of 9 and 17 get enough calcium, according to the recent NIH panel, because many are shunning dairy products in favor of soda. This imperils their ability to build bone mass upon which to draw as they age.

It’s easy to see how this one got started, because innumerable studies have shown that American diets are woefully deficient in calcium, the main building block of bone. Calcium is essential at all stages of life, for building bone mass early in life and for reducing bone loss thereafter. Only 10 percent of girls between the ages of 9 and 17 get enough calcium, according to the recent NIH panel, because many are shunning dairy products in favor of soda. This imperils their ability to build bone mass upon which to draw as they age.

People who never achieve maximum bone growth in their youth have fewer reserves and may drop to perilously low levels of bone density earlier than those who have developed thicker bones. That’s why adequate calcium is critical for children and teenagers.

But what’s lost in the consume-more-calcium campaigns are two important messages: that calcium alone does not appear to prevent fractures in most women, and that too much calcium may be harmful.

Recently the National Academy of Sciences, concerned that too many people were getting too much calcium from fortified foods and supplements, set an upper limit on intake at 2,500 mg per day. Some prominent scientists, including Walter Willett, a veteran nutrition researcher at the Harvard School of Public Health, contend that calcium consumption may not be so desirable and that promoting it “has become like a religious crusade.”

One study of 70,000 American nurses, co-authored by Willett, found that women with the highest calcium consumption from dairy products actually had more fractures than those who drank less milk. And fracture rates in China and other Asian countries, where consumption of milk and calcium in other dairy products is low (and where women tend to be small-boned and thin, a widely accepted risk factor for osteoporosis), are much lower than in the United States and Scandinavian countries, where calcium consumption, particularly of dairy products, is higher.

One study of 70,000 American nurses, co-authored by Willett, found that women with the highest calcium consumption from dairy products actually had more fractures than those who drank less milk. And fracture rates in China and other Asian countries, where consumption of milk and calcium in other dairy products is low (and where women tend to be small-boned and thin, a widely accepted risk factor for osteoporosis), are much lower than in the United States and Scandinavian countries, where calcium consumption, particularly of dairy products, is higher.

Some researchers believe that it’s not a surfeit of milk or other dairy products that’s the culprit, but diets high in animal fat, which can leach vital nutrients from bones.

None of this negates the importance of calcium, both in building bone mass early in life and in minimizing bone loss after menopause. Women lose bone mass more rapidly after menopause because of declining levels of estrogen.

And some experts add that the calcium mania may obscure an even more important non-drug treatment: exercise.

The NIH panel noted that “there is strong evidence that physical activity early in life contributes to higher peak bone mass.” In addition, the panel found, “clinical trials have shown that exercise reduces the risk of falls by approximately 25 percent.”

Falls are a major cause of fractures in people with osteoporosis, most of them elderly women. Exercise has been proven to improve balance and gait, which are important in preventing falls.

Take-home message: Calcium is necessary but not sufficient to protect bones. It’s important to get the recommended daily intake at all ages, preferably from dietary sources, as part of an overall approach to preventing osteoporosis and fractures. And it’s important not to exceed recommended limits.

MYTH #2

Getting a Baseline Bone Density Test at Menopause Is Essential

Not according to most experts, despite claims by some physicians and drug companies.

The National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends universal screening for women without risk factors or fractures at age 65–when the noninvasive test, which measures bone density at a particular site such as the hip, spine or heel–is covered by Medicare.

Both the recent NIH panel and the U.S. Preventive Health Services Task Force, an influential independent panel of primary care physicians, have decided against endorsing mass bone density screening for any age group. The groups cited variations in the tests themselves, questions about their accuracy and a lack of evidence that expensive testing is justified in patients without significant risk factors or those who have not already broken a bone.

“It’s very hard to tease apart what’s normal bone loss associated with aging and when it escalates to a disease,” said Pamela Boggs, director of education for the North American Menopause Society, a group of physicians and educators. As Boggs noted, there is no agreement about what constitutes “normal” bone density in older women.

Confusion about bone density tests abounds among physicians, noted Oregon’s Mark Helfand, because the results are imprecise and hard to interpret.

In addition, studies have failed to prove that bone density at age 50 predicts fractures later in life, observed Amy Allina, policy director for the National Women’s Health Network, a Washington-based advocacy group.

That’s because osteoporosis and fractures, while related, are not synonymous. Some women with high bone density have fractures, while others with low bone density never do. Bone density is only one factor–admittedly an important one–that influences the risk of fractures. The other important determinants are bone quality–the internal architecture of bones, which cannot be measured–and the rate of bone loss, which is difficult to gauge.

Even so, a growing number of women are getting bone density tests in their forties and fifties, often at the suggestion of their physicians. Last year, according to Allina, Merck officials reported that 3.5 million bone density tests had been performed in 1999, compared with about 100,000 tests in 1995.

Many women are understandably upset when they are told that the test shows they have “osteopenia”–bone mass that is low, but not low enough to be considered osteoporotic.

“This real scary word gets attached to something that may not be bone loss at all,” said endocrinologist Bruce Ettinger, director of research for Kaiser Permanente’s Medical Care Program in San Francisco.

Ettinger notes that there’s no way to tell from a bone density test whether a woman at 55 who meets the definition of osteopenia has the same bone mass she did at 25–and hasn’t lost any bone–or whether her bones are thinning rapidly, which would place her at higher risk for fracture.

“If someone is 5[-foot-]3 at menopause and has been since adolescence, we don’t say she’s lost height,” Ettinger said.

Much of the confusion about the meaning of low bone mass and osteoporosis stems from the new definitions drafted in 1994 by a working group of the World Health Organization (WHO). These definitions, devised for epidemiological rather than clinical reasons, greatly expanded the number of people considered to have osteoporosis.

Under the old standard, a person was deemed to have osteoporosis if she had broken a bone after little or no trauma. Under the new definition, a person is considered to have osteoporosis if her bone density is 2.5 standard deviations–or steps–below the average density of a healthy 35-year-old woman. That is expressed as a “T” score, which, in the case of such a woman, would be -2.5. Women who take a bone density test also get a “Z” score, which tells them how their bone density compares with women of the same age.

Osteopenia is defined as more than one standard deviation (a T score of -1) below the hypothetical healthy 35-year-old.

What’s wrong with this definition?

Plenty, according to many experts, who say it’s overly broad. And the revised definition does not “specify the technique by which or the site at which bone mineral density should be measured,” noted British physician Richard Eastell in a 1998 review article published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

To Love, the new WHO definition is similar to defining anyone over 5 feet as tall, rather than setting the limit at 5 feet 10 inches: The lower threshold includes a lot more people.

But, Love added, if getting a bone density test at menopause motivates a woman to start exercising, quit smoking and pay attention to her diet, it may not be a bad thing. The downside, she observed, is that the results may not mean much and may unnecessarily alarm some women, spurring them to take unnecessary drugs–for which the long-term risks are unknown–to treat a problem they may not have.

Take-home message: For most women, a bone density test at menopause is not useful because the majority of women under 65 have an insignificant risk of fracture. There is insufficient evidence that current bone density tests are a sufficiently reliable way to predict bone loss decades later.

MYTH #3

Half of White Women Over 50 Will Have A Fracture in Their Lifetime

This frightening statistic is a virtual mantra among osteoporosis advocates, but it doesn’t mean what many people think: that one woman in two in their fifties or sixties will break a bone because of osteoporosis.

The truth is that if you live long enough, you may break a bone because of osteoporosis. That’s because the risks of osteoporosis and fractures increase with age. Most fractures are concentrated in women over age 70.

The lifetime risk of having a hip, spine or wrist fracture for a white woman is 39 percent, according to Mayo Clinic epidemiologist L. Joseph Melton, while the remaining 11 percent are fractures in other places such as the ankle. That’s based on a life expectancy of 79 years. Black and Hispanic women are at much lower risk for all fractures for unknown reasons; most studies have been conducted only with white women.

But lifetime fracture risk, some experts contend, is widely misunderstood and needlessly alarming.

“The lifetime risk of fracture tells you very little,” said Oregon’s Mark Helfand. “It needs to be taken with a grain of salt. The truth is that if you live to be 90, there’s a high chance that when your mind goes you’ll fall down and break your hip. You are going to die of something at 90.”

“Lifetime risk is a way to scare people, and it’s been very effective in doing that,” agreed Kaiser’s Bruce Ettinger. “Most fractures occur between the ages of 75 and 80.” The average age of hip fracture patients is 80.

As Love notes, all fractures are not created equal, even though they are lumped together. A wrist fracture is an annoying nuisance that heals after a few weeks and does not permanently impede mobility, while a hip fracture can.

Take-home message: Lifetime risk numbers can be misleading because the risk of osteoporosis rises with age. For most women the chance of breaking a bone at 55 is remote, while the chance of a fracture at 85 is significant. Don’t let misleading lifetime risk numbers steer you into unnecessary treatment.

MYTH #4

Hip Fracture Equals Nursing Home Equals Death

There’s no question that people with hip fractures often wind up in nursing homes. Much of the coverage of osteoporosis in newspapers and magazines includes a statistic commonly cited by the National Osteoporosis Foundation: 20 percent of women who break a hip and end up in a nursing home are dead within a year.

“When we say that 20 percent are dead within a year, that’s true,” said Mayo’s Melton, “but at least half of them would have been dead within a year anyway. It’s fair to say that osteoporosis played a part in their deaths, but it didn’t cause it.”

That’s because many of these women are in poor health, suffering from dementia, poor eyesight and other serious medical problems: among this group, the use of powerful, long-acting tranquilizers or anti-psychotics that can trigger falls is common. And falls can be an indicator of declining health, overmedication or both.

Breaking a hip, in other words, is often a marker for generally frail health. It tips what has been a precarious balance.

According to the NIH consensus report, one-third of hip fracture patients regain the level of functioning they had before the fracture, while one-third require placement in a nursing home. The rest are somewhere in between.

Take-home message: It’s not the hip fracture that leads to death, it’s the fact that many women who are frail, demented or suffering from other serious health problems often fracture their hips. Women who get hip fractures and are relatively healthy rarely die from the fracture itself.

MYTH #5

Menopause Is the Most Important Cause of Osteoporosis

That’s the implication of some drug ads and a major reason women begin taking hormone replacement therapy (HRT) at menopause.

In fact, one of the most important causes of osteoporosis is aging.

Everyone loses bone mass as they age. It’s not unlike needing reading glasses: Virtually everyone needs them in middle age because the eye loses its ability to focus.

The association of estrogen and menopause with osteoporosis may stem from the fact that many bone studies have been done on women whose ovaries were removed, not those who underwent normal menopause, said Love, noting that surgical menopause seems to accelerate bone loss.

Women do lose estrogen at menopause, which is important in maintaining bone density, she added, but the rate of loss varies. And results of the definitive study of whether estrogen replacement therapy prevents hip fractures won’t be available for several more years.

In the meantime some osteoporosis experts advise that for most women without significant risk factors, it’s probably useless and potentially dangerous to start taking a drug at menopause in the hope of preventing fractures decades later. As Love put it, “You could be trading a wrist fracture for breast cancer.”

Although estrogen reduces the risk of certain kinds of fractures while you’re taking it–and only while you’re taking it since there’s no evidence of a residual benefit–studies have shown that long-term users have an elevated risk of breast cancer.

Most women who take HRT do so for a variety of reasons, including osteoporosis prevention, treatment of hot flashes and other symptoms. For those most concerned with fracture prevention, it might be best to delay HRT until 65 or 70, Love suggested, when the risk of osteoporosis rises. That way the length of time taking hormones would be minimized, thereby reducing the risk of breast cancer associated with prolonged use of estrogen.

“We try to encourage people not to think about treatment early,” said osteoporosis expert Robert Lindsay, a New York internist. “Certainly there are very few women in their fifties with a bone density low enough to warrant treatment” with bone-building drugs.

Before age 65, Lindsay added, most women don’t need treatment for osteoporosis, other than advice about getting enough calcium, exercising and minimizing risks. “After 65 it becomes more arguable for intervention; by age 75 to 80 about half of all women may need intervention,” he said.

The National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends that women with T scores below -2 and no risk factors be treated for osteoporosis; it also recommends treatment for women with established risk factors and scores below -1.5.

“I’d rather say to somebody to wait until they have really low bone density” so they take bone-building drugs for the shortest amount of time possible, Lindsay added. That’s because none of the new bone-building drugs have been studied for longer than four years and all have potentially serious side effects, such as esophageal ulcers or blood clots.

Take-home message: Menopause contributes to osteoporosis but is not the chief cause. For most women in their forties and fifties, drugs taken largely to prevent osteoporosis may carry more risks than benefits.

Real Treatment

Until recently, post-menopausal women seeking treatment for osteoporosis had few options other than estrogen replacement and calcium supplements.

Both are still widely used, but they’ve been augmented by several new and immensely profitable medications that retard bone loss and prevent fractures. Women who take any of these prescription drugs also must be sure to get at least 1,200 mg of calcium from food and supplements and at least 400 international units of vitamin D. They also are advised to engage in weight-bearing exercise (walking, running or weightlifting; not swimming or bicycling).

Most prescription medications for osteoporosis increase bone density by about 8 percent and all reduce the chance of fractures. But important questions about the drugs remain unanswered. With the exception of estrogen, none of the medicines has been studied for longer than about four years, which means that their long-term safety and effectiveness are unknown.

Consumers contemplating drug therapy should keep in mind that the ads for these medicines typically make them sound more impressive than they actually are. That’s because the ads usually highlight the relative risk or benefit. That percentage is much higher than the absolute, or actual, benefit or risk.

Take Fosamax, which according to its label reduces vertebral fractures by almost half–48 percent compared to a placebo. That’s true and it sounds impressive. But here’s the actual or absolute reduction in fractures: 2.3 percent. In a clinical trial, 2.5 percent of 1,545 women taking Fosamax suffered a fracture, compared with 4.8 percent of 1,520 patients who got a placebo.

It’s also important to remember that none of the medicines is a cure for osteoporosis. None builds new bone, the elusive goal of any future osteoporosis drug. One promising new medication, parathyroid hormone, is expected to be submitted for approval to the Food and Drug Administration later this year. It does generate bone growth, noted Robert Lindsay, a New York internist and a founder of the National Osteoporosis Foundation.

Such measures as taking calcium, exercising and eliminating environmental hazards like throw rugs are equally important in preventing fractures, experts emphasize.

Few studies of exercise and its relationship to bone density or fractures exist, although the NIH consensus panel noted that some researchers have found weight-bearing exercise to be effective in reducing the risk of falls and in preserving bone density.

“The single most important thing women can do is to take calcium and vitamin D and get exercise,” said osteoporosis researcher Deborah T. Gold, associate professor of medical sociology at Duke University School of Medicine.

Calcium, endorsed as both treatment and preventive, is most easily obtained from dairy products but is present in other foods as well as supplements. An eight-ounce glass of milk contains about 300 mg, the same amount as a serving of fortified orange juice. A three-ounce portion of canned salmon contains about 167 mg, compared with 200 mg in a cup of fresh cooked turnip greens. Nutrition labels typically list calcium content. Experts believe it’s preferable to get as much as your calcium as possible from food rather than from supplements, because it’s absorbed more completely. But taking supplements is better than not getting enough calcium.

Below is a primer on common osteoporosis drugs:

* ESTROGEN The most widely used drug for prevention. Available in various forms, sometimes with progesterone added to reduce the risk of endometrial cancer. Brand names include Premarin, Estrace, Prempro.

What It Does: Precise mechanism of action is unknown, but estrogen appears to slow the rate of bone loss by replacing the female sex hormone, levels of which decline at menopause.

Downside: Can increase the risk of breast cancer, cause blood clots, weight gain, headaches. Fracture prevention applies only to current users: Women who stopped taking estrogen had no difference in bone density or fractures than women who never took it, even if they took the drug for 10 years.

Effectiveness: Definitive results on hip fracture reduction await the outcome of the Women’s Health Initiative, a major federal study to be released in about 2007. Smaller studies have found that it reduces hip and wrist fractures by 60 percent, a number extrapolated from bone density studies. The FDA has no figures for absolute risk reduction because the data are based on projections.

Approximate monthly cost: $24-29.

* BISPHOSPHONATES Fosamax (alendronate); Actonel (risedronate).

What They Do: These new non-hormonal drugs target the skeleton (not other parts of the body, as does estrogen) by binding permanently to the surface of bone and slowing bone loss but not halting it. Approved for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis, they are typically prescribed for women who have been diagnosed with osteoporosis, particularly those who have already broken a bone and are unable or unwilling to take estrogen.

Downside: Unwavering adherence to a strict regimen is required to prevent serious stomach problems and ensure absorption. Among other things, users must remain upright for at least 30 minutes after taking their morning pill. Gastrointestinal problems, some of them serious, have been reported.

Effectiveness: Fosamax: relative risk reduction for all fractures is 22 percent; absolute risk reduction, 3.3 percent. In a clinical trial, 12.9 percent of 1,545 women taking the drug broke a bone, compared with 16.2 percent of 1,521 women who took a placebo. Actonel: relative reduction in risk of vertebral fractures is 41 percent; absolute risk reduction 5 percent. In a clinical trial, 16.3 percent of 678 women who took a placebo had a vertebral fracture within three years, compared with 11.3 percent of 698 Actonel users.

Approximate Monthly Cost: Fosamax: $55-70; Actonel: $51-55.

* SELECTIVE ESTROGEN RECEPTOR MODULATORS (SERMS) Evista (raloxifene).

What It Does: Approved for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in post-menopausal women, this drug mimics estrogen, possibly in the way it retards bone loss, but unlike estrogen it does not increase cancer risk. Studies are underway to determine if it reduces breast cancer risk.

Downside: Side effects include leg cramps, intensified hot flashes and increased risk of blood clots.

Effectiveness: Reduces relative risk of first vertebral fracture by 55 percent; 2.4 percent absolute risk reduction. In a clinical trial 4.3 percent of 1,457 women who took placebo suffered vertebral fracture, compared with 1.9 percent of 1,401 who took the drug.

Approximate Monthly Cost: $60-76.

* CALCITONIN Miacalcin, Calcimar.

What They Do: Approved only for treatment of women at least five years past menopause. Calcitonin, a hormone produced by thyroid cells, is available as a nasal spray or by injection. Works by blocking cells that cause bone loss. Drug may ease back pain caused by vertebral fractures.

Downside: Nausea, nasal irritation but fewer side effects than other medications.

Effectiveness: Less effective than other drugs, but may be better at reducing back pain.

Approximate Monthly Cost: $59-69.

* CALCIUM SUPPLEMENTS

Calcium citrate, calcium phosphate, calcium carbonate (the cheapest and most popular form) sold over-the-counter under numerous brand names. Look for added vitamin D, which is essential for calcium absorption.

Adults need 1,000-1,500 mg per day of calcium but should avoid more than 2,000 mg, which could cause kidney stones. Avoid more than 800 units of vitamin D.

What They Do: Adequate intake helps maintain bone density and reduce fractures.

Downside: Constipation and, more rarely, kidney stones.

Effectiveness: While vital to attaining and preserving bone mass, cannot by itself stop excessive bone loss.

Approximate Monthly Cost: $4-12.

Sources: National Osteoporosis Foundation, American Medical Association, National Women’s Health Network, Food and Drug Administration, AARP Pharmacy Service

The Real Risks

More than two dozen risk factors have been linked to the development of osteoporosis. While researchers are still debating which ones matter most, what follows is the current consensus on major risks. This list doesn’t include risk factors for secondary osteoporosis, which is the result of genetic or endocrine disorders, kidney disease, alcoholism or prolonged use of certain drugs such as corticosteroids to treat various diseases including asthma or arthritis.

The National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends treatment for women who score below -1.5 on a bone density test and also have risk factors other than being female and post-menopausal.

* Being female.

Eighty percent of people with osteoporosis are women. There are several reasons: women live longer; men have heavier bones; and women experience more rapid loss of bone density after menopause because of declining levels of estrogen, while bone loss in men typically occurs more gradually.

* Race.

For reasons that are unclear, white and Asian women have thinner bones than do black and Hispanic women (although Asian women have half the risk of hip fracture of their white counterparts, even though they tend to be small-boned and thin). A 50-year-old white woman has a lifetime risk of hip fracture of about 16 percent, compared with a 6 percent risk for an African American woman.

* Family history.

There is evidence that bone density and bone quality (composition and strength) may be largely inherited. If your mother or sister had osteoporosis or broke a bone before age 80, you are at higher risk.

* Previous fracture.

If you’ve already broken a bone in an accident with little or no trauma–a fall, not a car crash–you’re at elevated risk.

* Being small-boned or thin (weight less than 127 pounds).

Here’s one case in which obesity is protective of a disease. Your bones do more work when they lug around more weight, there’s more estrogen in fat and there’s more padding to protect bones if you fall. But there’s a confounding variable: small bones automatically register lower on bone density tests even if they’re not thinner “which makes small bones look even worse even when they’re not,” according to Mayo Clinic epidemiologist L. Joseph Melton.

* Smoking.

Add osteoporosis to the long list of cigarette-induced ills. Nicotine appears to impair calcium absorption.

Other risk factors include low calcium intake, physical inactivity, heavy alcohol consumption (more than two drinks per day) and history of anorexia.

Sources: NIH Consensus Conference Statement 2000; National Osteoporosis Foundation;, National Women’s Health Network

Recommended Calcium Intakes

Age Mg/Day

9-18 1300

19-50 1000

51-older 1200

SOURCE: National Academy of Sciences